We describe a computational system for automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing using fourteen different measures that have been explored or proposed in studies of second language development. The system takes a written language sample as input and produces fourteen indices of syntactic complexity of the sample based on these measures. The system is designed with advanced second language proficiency research in mind, and is therefore developed and evaluated using college-level second language writing data from the Written English Corpus of Chinese Learners (Wen et al. 2005). Experimental results show that the system achieves a very high reliability on unseen test data from the corpus. We illustrate how the system is used in an example application to investigate whether and to what extent each of these measures significantly differentiates between different proficiency levels.

Keywords: developmental index, learner corpus analysis, second language development, second language writing, syntactic complexity

Syntactic complexity is manifest in second language writing in terms of how varied and sophisticated the production units or grammatical structures are (Foster & Skehan 1996, Ortega 2003, Wolfe-Quintero et al. 1998). It has been considered an important construct in second language teaching and research, as development in syntactic complexity is an integral part of a second language learner’s overall development in the target language. A large number of different measures have been proposed for characterizing syntactic complexity in second language writing.

Most of these seek to quantify one of the following in one way or another: length of production units (i.e. clauses, sentences, and T-units, as defined in Section 3.2), amount of embedding or subordination, amount of coordination, range of surface syntactic structures, and degree of sophistication of particular syntactic structures (Ortega 2003). Notably, the specific set of measures proposed for second language development research differs from the set of measures widely adopted in first language development studies (for an overview of these measures, see, e.g., Cheung & Kemper 1992 and Kreyer 2006), although some overlap exists. While measures that gauge length of production units are common in both sets, many first language syntactic complexity measures rank syntactic structures based on patterns of syntactic development or frequency of use, e.g. Developmental Level (D-Level) (Covington et al. 2006, Rosenberg & Abbeduto 1987), Developmental Sentence Scoring (DSS) (Lee 1974), and Index of Productive Syntax (IPSyn) (Scarborough 1990). Others quantify the demand of cognitive processing of different types of syntactic constructions, including node-counting algorithms that count the number of nodes in the phrase markers of syntactic constructions, e.g. Frazier’s (1985) local nonterminal count and Yngve’s (1960) depth algorithm, and word-counting algorithms that are based on ratios involving constituent lengths in number of words (e.g. Hawkins 1994). This instrumental difference is not surprising, as first and second language development are themselves very different processes.

A fundamental question that many second language development studies have attempted to answer is to what extent the many syntactic complexity metrics that exist are valid and reliable indices of second language learners’ developmental level or global proficiency in the target language. This is a crucial question, as the validity of the syntactic complexity metrics directly bears upon the validity of the research results obtained using them. In an effort to address this issue, researchers have conducted cross-sectional studies to investigate between-proficiency differ- ences in syntactic complexity of second language production (e.g. Bardovi-Harlig & Bofman 1989, Ferris 1994, Henry 1996, Larsen-Freeman 1978) as well as longitudinal studies to track the learners’ developmental changes in syntactic complexity of second language production over an extended period of time (e.g. Ishikawa 1995, Ortega 2000, Stockwell & Harrington 2003).

Intuitively, in searching for the best syntactic complexity measures as indices of second language development, it is desirable to directly compare the full range of measures under consideration using multiple sets of large-scale learner corpus data that encode rich, meaningful learner and task information. Similarly, in using syntactic complexity measures to assess second language proficiency, it is prefer- able to apply the full range of measures of interest to the teacher or researcher to as much relevant learner data as necessary and possible. Unfortunately, this has not been an easy task in the past, due to the lack of reliable computational tools that can automate second language syntactic complexity measurement and the labor-intensiveness of manual analysis. As a result, previous studies typically examined few measures and analyzed relatively small amounts of data. For example,476 Xiaofei Lu among the twenty-five second or foreign language development studies reviewed in Ortega (2003), four studies examined four to five different measures, and the rest examined one to three measures only. In addition, the number of language samples analyzed in all of the twenty-one cross-sectional studies reviewed in Ortega (2003) ranged from 16 to 300, with a mean of 84 and a standard deviation of 74, and the number of words in those language samples ranged from 70 to 500, with a mean of 234 and a standard deviation of 110. It is not always straightforward to pool the research results reported in different studies that examined different sets of measures using different datasets in research syntheses, as there is a significant amount of variability and inconsistency among those studies in terms of choice and definition of measures, operationalization of proficiency, language task used in data collection, corpus size, etc. (Ortega 2003, Wolfe-Quintero et al. 1998). To facilitate application of the large set of syntactic complexity measures of interest to second language researchers to large-scale corpus data, it is clearly necessary to develop computational tools that can automate analysis of syntactic complexity in second language production using those measures.

Several computational systems for automatic syntactic complexity analysis exist. For example, computerized profiling, a software package designed by Long et al. (2008) for child language research, incorporates the capability to automate the computation of DSS and IPSyn using shallow part-of-speech and morphological information. Coh-Metrix, an online toolkit developed by Graesser et al. (2004) for assessing text coherence, includes the following three indices of syntactic complexity of a text: mean number of modifiers per noun phrase, mean number of higher level constituents per sentence, and the number of words appearing before the main verb of the main clause in the sentences of a text. D-Level Analyzer, an automatic syntactic complexity analyzer developed by Lu (2009) for child language acquisition research, implements the revised Developmental Level scale using deep syntactic parsing. To the best of our knowledge, however, the measures incorporated in existing systems are primarily those proposed for and employed in first language acquisition or psycholinguistic research, whereas the wide array of measures of particular interest to second language development researchers have not been systematically automated.

The goal of this paper is to fill this important gap. We describe a computational system for automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing using fourteen different measures that have been explored or proposed in the second language development literature. The system takes a written English language sample in plain text format as input and produces fourteen indices of syntactic complexity of the sample based on these measures. The system is designed with advanced second language proficiency research in mind, and is therefore developed and evaluated using college-level second language writing data selected from the Written English Corpus of Chinese Learners (WECCL) (Wen et al. 2005). Experimental results show that the system achieves a very high reliability on unseen test data from the corpus. We illustrate how the system is used in an example application to investigate whether and to what extent each of these measures significantly differentiates between different proficiency levels.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the choice and definitions of the complete set of syntactic complexity measures incorporated in the computational system. Section 3 describes the structure and specifics of the computational system. Section 4 evaluates the performance of the system using college-level second language writing samples selected from the WECCL. Section 5 illustrates how the system is used in an example application to analyze large-scale data from the WECCL to identify which of these measures significantly discriminate proficiency levels. Section 6 concludes the paper with a discussion of the implications of the research results and directions for further research.

Question

What is the goal of the paper described in the passage?

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

The fourteen syntactic complexity measures incorporated in the computational system are selected from the large set of measures reviewed in Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998) and Ortega (2003). Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998), in a large-scale research synthesis, examined over one hundred developmental measures of accuracy, fluency, and complexity (including lexical and syntactic complexity) employed in thirty-nine second language writing development studies. They compared the results across all the studies that have used each measure with the aim of identifying the measures that best index second language learners’ developmental levels. Six of the syntactic complexity measures Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998) examined were later investigated in greater depth in Ortega (2003) in a more focused research syn- thesis. Ortega compared the results reported for each of the six measures among twenty-five college-level second and foreign language writing studies with the aim of determining the impact of sampling conditions on the relationship of syntactic complexity to proficiency, the magnitudes at which between-proficiency differences reach statistical significance, and the length of instruction period required for significant changes in syntactic complexity of second language writing to occur. While the specific syntactic complexity measures used in second language studies varied greatly, these two research syntheses represent a fairly complete picture of the repertoire of measures that second language development researchers draw from and therefore constitute a natural source for choosing the measures to be incorporated in the computational system.

The final set of syntactic complexity measures selected consists of the six measures covered in both Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998) and Ortega (2003), another five measures that were shown by at least one previous study to have at least a weak correlation with or effect for proficiency, and three other measures that have not been explored in previous studies but were recommended by Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998) to pursue further. These measures can be categorized into the following five types: The first type consists of three measures that gauge length of production at the clausal, sentential, or T-unit level, namely, mean length of clause (MLC), mean length of sentence (MLS), and mean length of T-unit (MLT). The second type consists of a sentence complexity ratio (clauses per sentence, or C/S). The third type comprises four ratios that reflect the amount of subordination, including a T-unit complexity ratio (clauses per T-unit, or C/T), a complex T-unit ratio (complex T-units per T-unit, or CT/T), a dependent clause ratio (dependent clauses per clause, or DC/C), and dependent clauses per T-unit (DC/T). The fourth type is made up of three ratios that measure the amount of coordination, namely, co- ordinate phrases per clause (CP/C), coordinate phrases per T-unit (CP/T), and a sentence coordination ratio (T-units per sentence, or T/S). The fifth and final type consists of three ratios that consider the relationship between particular syntactic structures and larger production units, i.e. complex nominals per clause (CN/C), complex nominals per T-unit (CN/T), and verb phrases per T-unit (VP/T). These measures and their definitions are summarized in Table 1. Definitions of the various production units and syntactic structures involved in computing these measures are discussed in Section 3.2 below.

In this section, we describe a computational system that incorporates deep syntactic parsing for computing the syntactic complexity of English language samples using the fourteen syntactic complexity measures discussed in Section 2. The system takes as input a written English language sample in plain text format and outputs fourteen indices of syntactic complexity of the sample based on the fourteen measures. This process is materialized in the following two stages: In the preprocessing stage, the system calls a state-of-the-art syntactic parser to analyze the syntactic structures of the sentences in the sample. The output is a parsed sample that consists of a sequence of parse trees, with each parse tree representing the analysis of the syntactic structure of a sentence in the sample. In the syntactic complexity analysis stage, the system analyzes the parsed sample and produces fourteen syntactic complexity indices based on the analysis, in two steps: The syntactic complexity analyzer first retrieves and counts the occurrences of all relevant production units and syntactic structures necessary for calculating one or more of the fourteen measures in the sample, and then calculates the indices using those counts.

As analyzing the syntactic complexity of a language sample involves identifying and counting the occurrences of a number of different production units and syntactic structures, it is necessary to analyze the syntactic structure of each sentence in the sample first. The system uses the Stanford parser (Klein & Manning 2003) for this purpose. Syntactic parsers generally require the input text to be segmented into individual sentences (with one sentence per line) and each sentence to be tokenized and part-of-speech (POS) tagged. In other words, a sentence needs to be broken into individual tokens (e.g. words, acronyms, numbers, punctuation marks, etc.), and each token needs to be annotated with a tag or label that indicates its POS category (e.g. adjective, adverb, preposition, etc.). However, the Stanford parser has built-in sentence segmentation, tokenization, and POS tagging functionalities, and therefore no other preprocessing of the raw input text is needed. For example, given the sentence in (1) taken from the WECCL, the parser generates the parse tree in (2), in which the labels used to indicate the POS, phrasal, and clausal categories are the same as those used in the Penn Treebank (Marcus et al. 1993). A parsed sample contains a sequence of such parse trees. As the Stanford parser is trained using native language data from the Penn Treebank, it is important to examine the difficulties it may encounter with second language writing data. This is discussed in Section 4.3 below.

Question

What tool does the system use for analyzing the syntactic structure of each sentence in the language sample?

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

Given the syntactically-parsed language sample, the syntactic complexity analyzer first retrieves and counts all the occurrences of nine relevant production units and syntactic structures in the sample, i.e. words, sentences (S), clauses (C), dependent clauses (DC), T-units (T), complex T-units (CT), coordinate phrases (CP), complex nominals (CN), and verb phrases (VP). For word counting, the analyzer retrieves the total number of tokens that are not punctuation marks. Since the sample is tokenized and all tokens, including punctuation marks, are POS-tagged as part of the parsing process, this task is relatively straightforward. To count the number of occurrences of the other eight units and structures, the system calls Tregex (Levy & Andrew 2006) to query the parse trees using a set of manuall defined Tregex patterns.3 Given a pattern that is written following the Tregex syntax, Tregex retrieves only those nodes that match the pattern from the input parse trees. The design of patterns that match the set of production units and syntactic structures we are looking for entails explicit definitions of these units and structures. As Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998) noted, many previous studies failed to provide such explicit definitions, and the definitions that have been presented were not always completely consistent with each other. In what follows, we describe the definitions adopted in this study and the Tregex patterns developed to operationalize them. In the current system, if competing definitions of the same unit or structure exist, we generally favor the one that appears to be most widely accepted or, in cases where no single definition is most theoretically appealing than others, the one that can be operationalized most accurately given the language technology at our disposal.

Sentences. A sentence is a group of words delimited with one of the following punctuation marks that signal the end of a sentence: period, question mark, exclamation mark, quotation mark, or ellipsis (Hunt 1965, Tapia 1993).4 This is compatible with the definition assumed by the sentence segmentation module in the Stanford parser. This definition is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (3), which simply matches a ROOT node, as the parse tree of a sentence always has one and only one ROOT node. For example, this pattern matches the ROOT node in

(2) that represents the sentence in (1).

(3) “ROOT”

Clauses. A clause is defined as a structure with a subject and a finite verb (Hunt 1965, Polio 1997), and includes independent clauses, adjective clauses, adverbial clauses, and nominal clauses. This is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (4), which matches a clausal node (S, SINV, or SQ) that immediately dominates a finite verb phrase, i.e. a VP that is immediately headed by a modal verb (MD) or a finite verb (VBD, VBP, or VBZ).5 For example, the pattern matches the two S nodes from the parse tree in (2) that represent the two clauses in the sentence in (1). Both of the two S nodes immediately dominate a VP that is immediately headed by a finite verb: use (tagged as VBP) in the case of the first S node and is (tagged as VBZ) in the case of the second one. Non-finite verb phrases are excluded in the definition of clauses (e.g. Bardovi-Harlig & Bofman 1989), but are included in the definition of verb phrases below. However, following Bardovi-Harlig & Bofman (1989), we allow clauses to include sentence fragments punctuated by the writer that contain no overt verb. The Tregex pattern in (5) matches FRAG nodes that represent such fragments.

(4) “S|SINV|SQ < (VP <# MD|VBD|VBP|VBZ)”

(5) “FRAG > ROOT !<< VP”

Dependent clauses. In line with the definition of clause, a dependent clause is defined as a finite adjective, adverbial, or nominal clause (Cooper 1976, Hunt 1965, Kameen 1979). This is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (6), which matches an SBAR node that immediately dominates a finite clause (as defined in the pattern in (4) above). As an example, the pattern matches the SBAR node in (2) that represents the dependent clause in the sentence in (1). This SBAR node immediately dominates an S node that in turn immediately dominates a VP headed by the finite verb is (tagged as VBZ).

(6) “SBAR < (S|SINV|SQ < (VP <# MD|VBD|VBP|VBZ))”

T-units. A T-unit is “one main clause plus any subordinate clause or nonclausal structure that is attached to or embedded in it” (Hunt 1970: 4). Given that it is only possible to search parse trees one by one using Tregex, we specify that a T-unit can only occur within a sentence punctuated by the writer (Homburg 1984, Ishikawa 1995). This definition is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (7), which matches a clausal node (S, SBARQ, SINV, or SQ) that satisfies one of the following two conditions: (i) it is immediately dominated by a ROOT node (i.e. it is a top-level independent clause), or (ii) it is the right sister of a clausal node and it is not dominated by an SBAR or VP node (i.e. it is a coordinate independent clause). For example, this pattern matches the first S node in (2), which is immediately dominated by a ROOT node, but not the second S node, which does not satisfy either of the two conditions. We also allow a T-unit to include sentence fragments punctuated by the writer (Bardovi-Harlig & Bofman 1989, Tapia 1993). This is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (8), which simply matches a sentence fragment punctuated by the writer.

(7) “S|SBARQ|SINV|SQ > ROOT | [$-- S|SBARQ|SINV|SQ !>> SBAR|VP]”

(8) “FRAG > ROOT”

Complex T-units. A complex T-unit is one that contains a dependent clause (Casanave 1994). This is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (9), which matches a T-unit (as defined in the pattern in (7)) that dominates a dependent clause (as defined in the pattern in (6)).8 For example, this pattern matches the first S node in (2), which is immediately dominated by a ROOT node (therefore a T-unit) and which dominates an SBAR node that represents a dependent clause (therefore a complex T-unit).

(9) “S|SBARQ|SINV|SQ [> ROOT | [$-- S|SBARQ|SINV|SQ !>> SBAR|VP]] << (SBAR < (S|SQ|SINV < (VP <# MD|VBP|VBZ|VBD)))”

Coordinate phrases. Only adjective, adverb, noun, and verb phrases are counted in coordinate phrases (Cooper 1976). These are captured using the Tregex pattern in (10), which matches an adjective phrase (ADJP), adverb phrase (ADVP), noun phrase (NP), or verb phrase (VP) that immediately dominates a coordinating conjunction (CC). As an example, this pattern matches the ADJP node in (11), which immediately dominates a CC node.

(10) “ADJP|ADVP|NP|VP < CC”

(11) (ADJP (JJ long)

(CC and)

(JJ invisible))

Complex nominals. Complex nominals comprise (i) nouns plus adjective, possessive, prepositional phrase, relative clause, participle, or appositive, (ii) nominal clauses, and (iii) gerunds and infinitives in subject position (Cooper 1976). These are operationalized using the Tregex patterns in (12), (13), and (14) respectively. The pattern in (12) matches an NP node that is not immediately dominated by another NP and that dominates an adjective (JJ), possessive (POS), prepositional phrase (PP), relative clause (S), participle (VBG), or appositive (an NP that is a left sister of another NP and that is not the immediate left sister of a CC).9 For example, this pattern matches the two NP nodes in (2) that represent the noun phrases a girl in our dorm and a spoiled child respectively. The pattern in (13) retrieves nominal clauses by matching an SBAR node in subject or object position (i.e. it is either an immediate left sister of a VP or is immediately dominated by a VP) that satisfies one of the following two conditions: (i) it immediately dominates a wh- noun phrase (WHNP) (e.g. what I like) or a complementizer (i.e. that or for tagged as a preposition, as in that you like to read), or (ii) it has an S node as its first child (i.e. a clausal object without a complementizer, as in I know you like to read). The pattern in (14) retrieves gerunds and infinitives in subject position by matching an S node that immediately dominates a VP headed by a gerund or the infinitive “to” and that is an immediate left sister of a VP (e.g. Saving energy is really important).

(12) “NP !> NP [<< JJ|POS|PP|S|VBG |<< (NP + CC)]”

(13) “SBAR [$+ VP | > VP] & [<# WHNP |<# (IN < That|that|For|for) |<, S]”

(14) “S < (VP <# VBG|TO) $+ VP”

Verb phrases. Verb phrases comprise both finite and non-finite verb phrases. This is operationalized using the Tregex pattern in (15), which matches a VP node that is immediately dominated by a clausal node. This restriction allows us to retrieve verb phrases immediately headed by a modal or auxiliary verb, e.g. is acting like a spoiled child, only once. For example, this pattern matches the first two VP nodes in (2), both of which are immediately dominated by an S node, but not the third VP node.

(15) “VP > S|SQ|SINV”

After the occurrences of the nine production units and syntactic structures in the syntactically-parsed writing sample have been retrieved using Tregex, the syntactic complexity analyzer uses the counts of those occurrences to compute the syntactic complexity of the writing sample. The final output is fourteen numeric scores, each of which is an index of the syntactic complexity of the writing sample based on one of the fourteen measures.

This system is freely available to the research community.10 It runs on UNIX-like systems (e.g. Linux, Mac OS, and UNIX) with the following recommended hardware requirements: a 750MHz Pentium III processor or better and 2GB or more Ramsey. The system consists of the following three components. The first two are freely available third-party tools, which need to be licensed and installed separately.

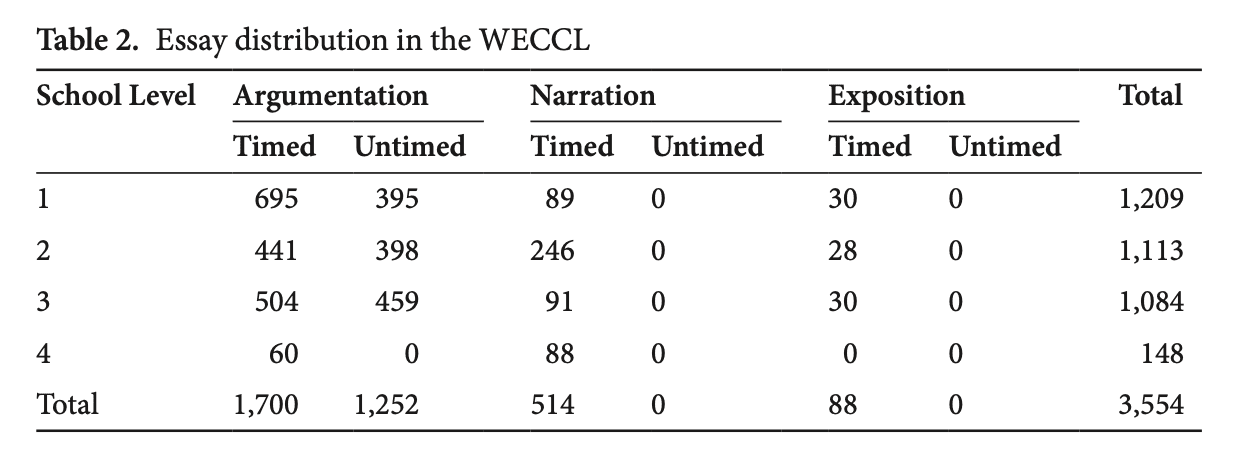

The computational system is designed with advanced second language proficiency research in mind, and is therefore developed and tested using college-level second language writing data selected from the Written English Corpus of Chinese Learners. This corpus comprises 3,554 essays written by English majors from nine different four-year colleges in China. These essays contain an average of 315 words, with a standard deviation of 87. Each essay is preceded by a header that provides the following information: mode (written), genre (argumentation, narration, or exposition), school level (year in college), year of admission (2000 through 2003), timing condition (timed or untimed), institution code, and length. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of the essays in terms of school level, genre, and timing condition.

We randomly selected 40 essays from the corpus, with 20 used for development and the other 20 reserved for testing. The development data was used for designing and revising the syntactic complexity analyzer, particularly the Tregex patterns, and the test data was used for evaluating the performance of the final system. Two trained annotators first independently labeled the boundaries of the production units and syntactic structures discussed in Section 3.2 (except words) in 10 of the 40 essays. The analyses of these 10 essays were used to assess inter-annotator agreement on the identification of each unit and structure. Following Brants (2000), we computed inter-annotator agreement using the standard metrics of precision, recall, and F-score, as in (16) through (18), where A1 and A2 denote the analysis by the first and second annotator respectively. Two structures are considered identical if they have the same start, end, and category label. Since a gold standard annotation is not involved in comparing the two annotators’ analyses, the interpretations of precision and recall are different from what they usually mean, and the most useful measure to look at is the F-score in this case.

As the results in Table 3 show, inter-annotator agreement on the eight production units and syntactic structures was fairly high, with F-scores ranging from .907 for complex nominals to 1.000 for sentences. Table 4 further shows that correlations between the syntactic complexity scores computed by the two annotators for the 10 individual essays are very strong, ranging from .912 for CT/T to 1.000 for MLS. The annotators indicated that the explicit definitions and the training provided to them were helpful. Discrepancies between the two annotations were resolved through discussion, and the other 30 essays were subsequently analyzed, each by one annotator. The annotators reported an average of two hours for analyzing each essay.

Question

What is the average time spent by the annotators to analyze each essay?

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

Tables 5 and 6 summarize the results of the system’s identification of the eight production units and syntactic structures on the development and test data respectively. Precision, recall, and F-score are computed using the same formula as in (16) through (18), except that A1 and A2 now denote the analysis by the system and that by the annotators respectively. As the results indicate, the system achieves a very high degree of reliability for identifying these units and structures, with F-scores ranging from .846 for complex nominals to 1.000 for sentences on the development data, and from .830 for complex nominals to 1.000 for sentences on the test data.

The system generally achieves a higher degree of reliability for identifying higher-level production units and structures, viz. sentences, T-units, clauses, and complex T-units, than lower-level ones, viz. dependent clauses, coordinate phrases, complex nominals, and verb phrases. This is probably not surprising. Our error analysis suggests that most of the errors produced by the system can be attributed to parsing errors that primarily involved attachment level or conjunction scope. Such parsing errors do not affect the identification of higher-level units and structures as much as they do lower-level ones. Specifically, as long as a parsing error is contained within the boundaries of a unit or structure, it will not affect the identification of the boundaries of that unit or structure. Take the following prepositional phrase attachment error as an example. In analyzing the verb phrase benefit a lot from the Internet in academic study, the parser mistakenly attaches the prepositional phrase in academic study to the noun phrase the Internet. This unavoidably causes the system to erroneously identify the Internet in academic study as a complex nominal. However, this structural misanalysis does not affect the identification of the boundaries of the verb phrase or the clause, T-unit, and sentence containing the verb phrase.

The error analysis also indicates that learner errors found in the corpus do not constitute a major cause for errors in parsing or in identifying the production units and syntactic structures in question. The data suggest that for advanced learners, problems with writing at the sentence (as opposed to discourse) level seem to reside more in idiomaticity (e.g. issues with collocation) than in grammatical completeness. In addition, most of the learner errors that do exist in the corpus (e.g. errors with determiners or agreement) are of the types that do not lead to structural misanalysis by the parser or misrecognition of the production units and syntactic structures in question by the system.

Finally, Table 7 summarizes the correlations between the complexity scores computed by the system and by the annotators for the individual essays. The correlations range from .845 for CP/C to 1.000 for MLS on the development data, and from .834 for CP/C to 1.000 for MLS on the test data. All of the correlations are significant at the .01 level. These strong correlations suggest that the system achieves a high degree of reliability in terms of the syntactic complexity scores it generates.

In this section, we describe an example application of the system where it is used in a preliminary study to analyze data from the WECCL to investigate which of the fourteen syntactic complexity measures significantly differentiate between different language proficiency levels. We are especially interested in identifying measures that progress linearly across proficiency levels with statistically significant between-level differences. Language proficiency has been conceptualized in many different ways, including program levels, school levels, holistic ratings, classroom grades, etc. (Wolfe-Quintero et al. 1998). Given the information available in the corpus, we conceptualize proficiency using school levels. The subset of data analyzed includes all of the 1,640 timed argumentative essays written by students at the first three school levels (see Table 2). Using timed argumentative essays only allows us to avoid potential effects of genre and timing condition. The fourth school level is excluded as the corpus contains a relatively small number of essays written by students at that level.

Table 8 summarizes the means and standard deviations (SD) of the syntactic complexity values of the timed argumentative essays at each of the first three school levels as well as the results of one-way ANOVAs of the means. Given that we are investigating fourteen measures and therefore performing fourteen tests on the same dataset simultaneously, we employ the Bonferroni correction to avoid spurious positives. This sets the alpha value for each comparison to .05/14, or .004, where .05 is the significance level for the complete set of tests, and 14 is the number of individual tests being performed. In cases where the one-way ANOVA reveals statistically significant between-level differences, the Bonferroni test, a post hoc multiple comparison test, is run to determine whether such differences exist between any two levels.

As the results indicate, six measures show statistically significant between-level differences at the adjusted alpha level of .004 and progress linearly across the three school levels. These are highlighted in Table 8 and comprise two length of production measures, MLC and MLT; two coordination measures, CP/C and CP/T; and two complex nominal measures, CN/C and CN/T. In terms of their ability to discriminate adjacent school levels, Bonferroni tests suggest that statistically significant differences are found between levels one and two as well as between levels two and three for MLC, but only between levels two and three for the other five measures. Two other measures, MLS and VP/T, also demonstrate statistically significant between-level differences but do not progress linearly. Bonferroni tests suggest that they both decline insignificantly from level one to level two and then increase significantly from level two to level three. Finally, statistically significant between-level differences are not found for the other six measures.

These preliminary results allow us to make an important observation with respect to the syntactic development of Chinese learners of English. Students at higher proficiency levels tend to produce longer clauses and T-units, not as a result of increased use of dependent clauses or complex T-units, but as a result of increased use of complex phrases such as coordinate phrases and complex nominals. For ESL writing instruction, this observation points to the importance of helping students engage with complexity more at the phrasal level and less at the clausal level as they advance to higher levels of proficiency.

Question

What is the observation regarding the syntactic development of Chinese learners of English based on the preliminary study?

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

We have described a computational system designed for automatic syntactic complexity analysis of second language writing samples produced by advanced learners, using fourteen different measures. The system was developed and tested using college-level second language writing data from the WECCL. Experimental results show that the system achieves a high degree of reliability in identifying relevant production units and syntactic structures from the essays as well as in computing the syntactic complexity indices for the essays. F-scores of unit and structure identification range from .830 for complex nominals to 1.000 for sentences on the test data, and correlations between the syntactic complexity scores computed by the system and the human annotators range from .834 for CP/C to 1.000 for MLS.The error analysis indicated that errors in unit and structure identification were primarily caused by parsing errors involving attachment level and conjunction scope. It is important, however, to note that the results were obtained on writing samples produced by advanced second language learners that have little or no difficulty with producing grammatically complete sentences. These results cannot be readily extended to writing samples that contain a large portion of grammatically incomplete sentences, such as those produced by beginner-level learners.

This system provides a useful tool to second language writing researchers for analyzing the syntactic complexity of any number of writing samples using any or all of the fourteen complexity measures, effectively eliminating the bottleneck on the size of the dataset that can be analyzed. The system also has significant implications for second language writing assessment and pedagogy. As Wolfe-Quintero et al. (1998) pointed out, developmental measures have useful potential applications in test validation, program placement, end-of-course assessment, and trait analysis of holistic ratings. ESL assessment studies have used developmental measures to validate placement tests (e.g. Arnaud 1992) and have analyzed syntactic features of ESL writing by learners at different second language proficiency levels as well as in comparison to first language academic writing (e.g. Ferris 1994, Hinkel 2003). As results from such studies are often used to inform learner placement and promotion decisions (Wolfe-Quintero et al. 1998), the ability to automate syntactic complexity analysis of large-scale writing data is highly desirable, because it is likely to lead to increased reliability of the results obtained. For second language writing teachers, the system can facilitate comparing syntactic complexity of writing samples produced by different students, assessing changes in syntactic complexity of one or more students after a particular pedagogical intervention, or tracking syntactic development of one or more students over a particular period of time. These practices can help teachers understand the syntactic development of their students and evaluate the effectiveness of pedagogical interventions aimed at promoting syntactic development.

Future research will focus on enhancement of the computational system and application of the system to second language writing development research.

First, the current system incorporates fourteen syntactic complexity measures and adopts the most commonly used definitions for relevant production units and syntactic structures. Enhancement of the system in terms of incorporating more syntactic complexity measures as well as providing options for valid alternative definitions of the production units and syntactic structures may help better meet the diverse needs of different second language writing teachers and researchers.

Second, through the example application described in Section 5, we have demonstrated how the system can be used to determine the extent to which different measures can differentiate between different proficiency levels. We envisage a wide range of applications of the system in second language writing development research. In particular, given large-scale learner corpus data that encode rich, meaningful learner and task information, the system can be used to analyze such data to answer important research questions on various aspects of the relationship between syntactic complexity and writing proficiency. For example, it is useful to investigate, on a large scale, the roles various variables play in this relationship, including conceptualization of writing proficiency (e.g. school levels, program levels, holistic ratings, etc.), sampling condition and criteria (e.g. task type, genre, timing conditions, instructional setting, etc.), and learner background (e.g. first language, learning strategy, etc.), among others. It is also important to understand how different syntactic complexity measures compare with and relate to each other as indices of second language development. Aspects that need to be investigated to achieve this understanding include the extent to which each measure discriminates different proficiency levels, the magnitude at which between-level difference in each measure becomes statistically significant, the patterns of development associated with each measure, and the strength of correlations between different measures or different sets of measures.

Last updated at